Pesticide residues in context

There’s been a lot of discussion in the news lately about glyphosate residues on food as they relate to Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs). First let me say that despite what some media headlines may lead consumers to think, the changes being proposed for glyphosate MRLs will not impact how Canadian farmers use glyphosate and these changes do not pose any health and safety risk for consumers.

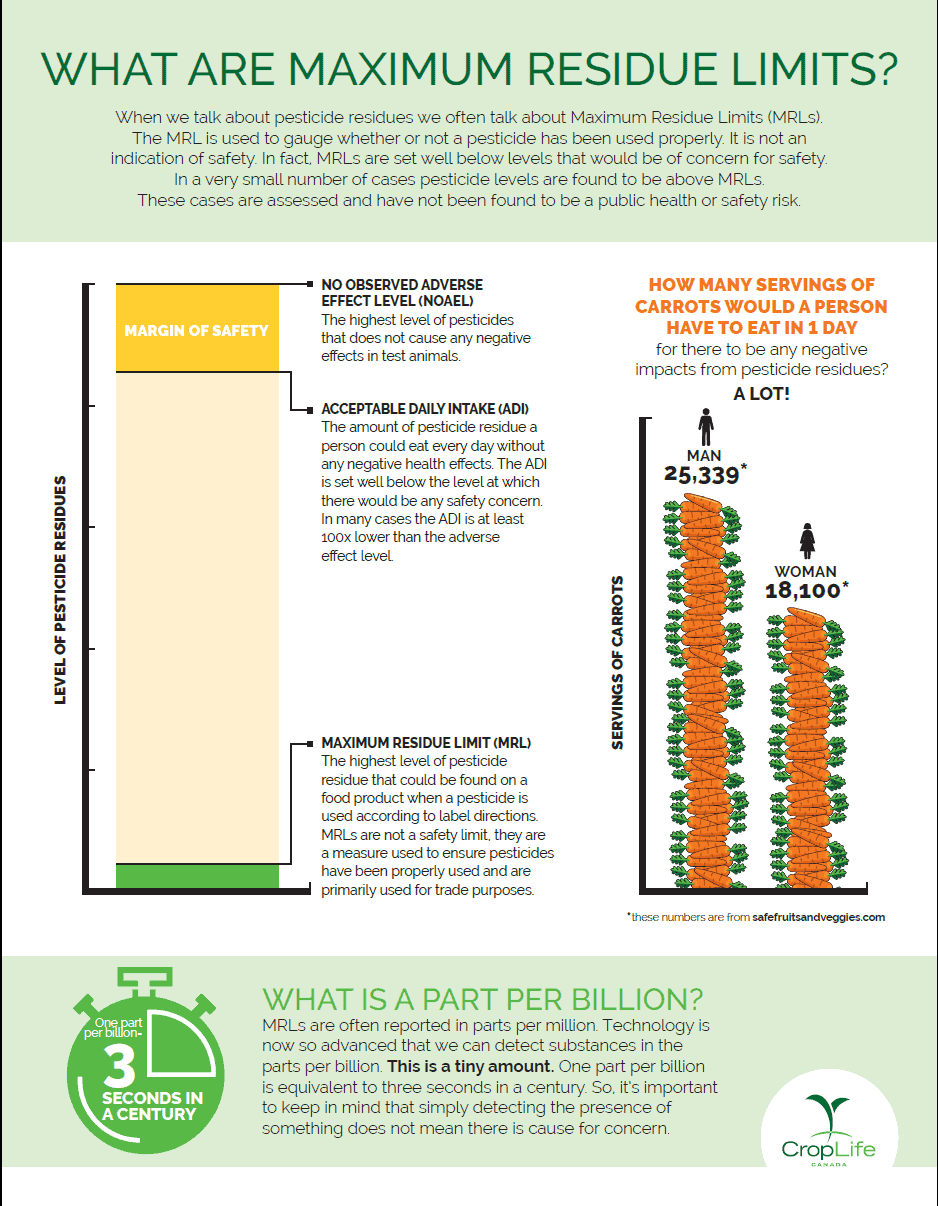

Let me talk a little bit about what MRLs are, exactly. An MRL is the maximum amount of pesticide residue that is allowed to remain on a crop when the product is used according to label directions. In Canada, MRLs are set by Health Canada. MRLs ensure that pesticides are being used as they are supposed to be by farmers. They are used to facilitate trade and they are not a measure of health and safety.

Individual countries establish MRLs to ensure that growers are using pesticides as directed. If a crop destined for export exceeds the MRL established by an importing country then that shipment may not be accepted. However, in cases where residue levels exceed an MRL, it does not mean there is a safety concern. In fact, most countries will conduct a risk assessment to determine if the crop with the MRL exceedance will be accepted. MRLs are often set 100 times or more below levels that would have any impact on human health.

It’s also important to understand that simply being able to detect a residue on a food item does not mean there is cause for concern. Regulatory agencies like Health Canada take into account how much potential exposure a person could have to a pesticide to accurately assess the risk. To put this into context, an adult woman could eat 850 servings of apples in one day without any negative impact from pesticide residues.

Detection technology is now so advanced that we can detect parts per billion – think one droplet of water in an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Essentially, if we go looking for trace amounts of any substance we can now find it, not because there’s more of it but because technology allows us to.

MRLs change on a regular basis for a number of reasons, including updates to a how a pesticide is used or to align with international standards. When it comes to the changes Health Canada is currently proposing, Canada is aligning with internationally agreed upon MRLs to facilitate global trade. Canada is a net global exporter of agricultural products – we export about three quarters of the soybeans and wheat we grow and more than 90 percent of the canola and pulses. Making sure we can get these products to their destinations is critically important for our economy and for those around the world that need what Canada produces.

Misaligned MRLs between trading partners can result in market instability and food waste due to massive delays or even entire shipments being turned away for what amounts to an administrative technicality.

Canada works closely with like-minded, science-based countries around the world to try to harmonize MRLs. In order for trade to flow freely around the world, we need consistent MRLs from one country to the next. Through the United Nations, there’s a body called Codex Alimentarius that sets MRLs for different crop-pesticide combinations according to internationally agreed upon science-based standards.

Codex is in the process of updating its MRLs for glyphosate on certain crops. The formal adoption of these MRLs, which was expected last year, has been delayed due to administrative challenges presented by the pandemic. These changes are expected to be adopted in the very near term and Health Canada’s proposal to update the Canadian MRLs will put us in line with these international standards.

The specific updates for MRLs related to cereals crops are intended to streamline how MRLs are presented but they will not actually change the MRL. As it stands, MRLs for wheat currently cover different milling fractions. The proposal will have the MRLs cover the raw commodity – i.e. wheat, barley or oats – rather than the processed ingredients. This aligns with how MRLs are set internationally.

Farmers must follow the label directions when it comes to the use of all pesticides, including glyphosate. It is the law. And Canadians can rest assured that all products imported into Canada must adhere to our high standards for pesticide residues on food.

It’s also important to remember that while glyphosate can be a politically charged topic, the reality is that it is one of the safest and most effective herbicides ever developed. There is more than 40 years’ worth of data to demonstrate the safety of glyphosate and no major regulatory authority in the world considers it to be a health risk when used according to label directions.

Health Canada, whose mandate is to protect the health and safety of Canadians, stands firmly behind the safety of glyphosate. It recently stated that it ‘left no stone unturned’ in looking at the science behind glyphosate and found no health or safety concerns associated with the use of glyphosate as directed.

The benefits of glyphosate don’t often make headlines but they are headline worthy. This important agricultural innovation has helped enable more environmentally sustainable farming practices by supporting the adoption of conservation and no-till farming, which has reduced greenhouse gas emissions and dramatically improved soil health. This supports regenerative agriculture.

The topic of MRLs is complex and nuanced – and connected to our global system of trade. It’s understandable that brought into the mainstream discussion it can cause confusion. But let’s be clear about one thing, when we are talking about MRLs we are talking about infinitesimally small amounts of residues that do not impact human health and safety.

Pierre Petelle,

President and CEO, CropLife Canada